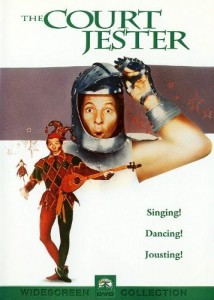

The opening song for the movie The Court Jester includes the memorable line: “Plot we’ve got, quite a lot!” And it is all the more memorable for being so true. (The Court Jester, if you have not seen it, really does have a great deal of plot, most of it both convoluted and humorous.)

I have always felt this was a good goal for a story to shoot for—to have lots of plot. Though, honestly, some of my favorite stories, especially children’s stories, do not have a great deal of plot. So the amount of plot, in and of itself, is not important.

Though, really, most of my favorite books have a lot of plot…a whole, big, humongous lot.

So the question arises: what makes for a great plot?

Last week, we looked at some of what Aristotle had to say on the topic. He addressed a number of aspects of plot, but not everything, so I thought it might be worth taking another brief look.

Basically, what great plots have in common is—they make sense, and they make you want to keep reading.

A plot might be complicated or simple, but to be a Great Book, one would hope at least that the plot makes sense. I say “hope” because there were be books on the St. John’s program whose plots leave something to be desired. But, clearly, the ones that have Great Plots makes sense.

Plot serves two functions: structure and impetus.

Structure is necessary so that the story hangs together. Without plot, a story is just a string of unrelated events, like a dream. No one thing particularly affects another. The human mind will attempt to impose structure on random chaos. There are a few “great” books that are famous for the structure imposed upon the dream-like prose by the readers—where the entire story becomes the ultimate “fan save.”*

*Fan save—the process by which fans of a story, comic, or show compensate for some lack of logic in the original by inventing clever explanations.

A good plot makes the individual scenes more interesting by helping draw the reader’s attention to the significant parts of them. A straightforward plot draws the reader’s attention to what is worth noticing. It helps bring meaning to the scene, to clue us in as to what we should notice or care about or why.

If a man walks down a road, with newspapers blowing about his feet, carrying a cup of coffee, we do not necessarily take much notice. If he is wearing a ring with the symbol of the rival ninja clan who is out to slay our father, the man becomes suddenly significant. If the newspaper catching on his shoe includes an article about the lost golden stallion medallion our main character has just been hired to locate, the scene becomes significant in another way.

In both cases, the existence of previous plot points—the rival ninja clans or the job to retrieve the stolen golden stallion medallion—make the scene of the man walking more significant, and, thus, more interesting.

A mystery plot uses the same technique to initially draw the reader’s attention to the wrong conclusions. It distracts from the truly significant points, while also touching on those points. When the reader looks back, from the conclusion, the structure now supports the real outcome, even though this was not obvious at the time.

The other purpose of plot is impetus—to draw the reader in and pull him along They make the reader ask “why” and then plow ahead, turning pages, to find the answer.

Sometimes we love a book, but when we put it down we have no impetuous to pick up again. Nothing in the book is leading us from one scene to another, even though each scene is enjoyable. When we pick it up again, we enjoy it again, but there is no push to find out what happens next.

Other times, books grab us and will not let go. We burn with the desire to discover what happens next. We have got to know!

John used to sit down to read me the latest thing he had written, always starting with the disclamer, “Now I want to remind you that this is unfinished. It breaks off in the middle.” One day, I asked him, “Why do you always say that? What are you picturing me doing when we get to the end?

As a response, he drew an adorable picture of a little girl her mouth open very wide, shouting, “What happens?”

I had to admit, I had probably done that. Sometimes, it is nearly unbearable to wait to find out what happens next, is it not?

We all yearn to write books no one wishes to put down. Yet, page-turning alone is not the mark of greatness. A book can be totally gripping, unputdownable, when you are reading it, but completely disappear from your thoughts the moment you put it down.

If the book does not make you think when you read it, it probably will not make you think later either. And many thrillers, many masters of the unputdownable do not want to let the reader go long enough to allow them to think. If they stop to think, they might put the book down, so better not to put any rough ideas, any speed bumps.

But if there is nothing to really make the reader pause and contemplate, then there is nothing to draw them back to it, to read it again and again.

I cannot think of any greater praise for a book than to reread it. A great plot makes the story worth reading both the first time and on all the return trips.